Safe Peripheral Management

by PatAn operating system works hard to abstract away details of the underlying hardware: virtual timers multiplex one physical timer to provide an unlimited number of alarms; bus interfaces seamlessly share one connection across multiple chips; processes operate independently of others running on the same machine. At the bottom of this visage, however, is real, physical hardware. Hardware that comes with expectations that do not always line up with software, and it can be tricky to ensure that those expectations are met, particularly as software gets more complex.

This post describes the recently merged PeripheralManager, which helps

software ensure it always accesses hardware correctly, and cleans up after

it’s done.

The key idea is to leverage Rust’s ownership model to manage access to

peripherals. By tying hardware access to ownership of a value, we can invoke

setup and cleanup code in a principled manner before and after all peripheral

accesses. For example, this let us move over 20 clock enable/disable calls

strewn about the SAM4L USART driver to just one invocation.

Further, by meting out access to a single static reference to the USART

hardware, we removed 35 unsafe blocks in the USART driver alone.

Memory-Mapped I/O

Most peripherals are implemented as memory mapped I/O (MMIO). The idea is that certain memory address are not backed by memory that you can read and write, but rather hardware peripherals that will perform certain actions: write this address to send a radio packet, read that address to get an ADC sample result, etc. In practice, this means that code usually models a peripheral as an array of words in memory at a certain location:

/// This is the SPI peripheral for the SAM4L, see §26.8

/// of the datasheet.

#[repr(C)]

pub struct Registers {

pub cr: WriteOnly<u32, Control::Register>,

pub mr: ReadWrite<u32, Mode::Register>,

pub rdr: ReadOnly<u32>,

pub tdr: WriteOnly<u32, TransmitData::Register>,

sr: ReadOnly<u32, Status::Register>,

...

/// This is how we attach the representation above to the

/// actual location in memory.

const SPI_BASE: StaticRef<SpiRegisters> =

unsafe { StaticRef::new(0x40008000 as *const SpiRegisters) };

For more information on how Tock models MMIO, check out our recent post on the new registers interface.

Ownership of MMIO Objects

Because MMIO affects underlying hardware, sometimes extra care is needed. For

example, on the SAM4L, if you attempt to read or write a peripheral while its

clock is disabled, the whole core will hang! Enter the PeripheralManager:

impl PeripheralManagement<pm::Clock> for SpiHw {

type RegisterType = SpiRegisters;

fn get_registers(&self) -> &SpiRegisters {

&*SPI_BASE

}

fn get_clock(&self) -> &pm::Clock {

&pm::Clock::PBA(pm::PBAClock::SPI)

}

fn before_peripheral_access(&self, clock: &pm::Clock,

_: &SpiRegisters) {

clock.enable();

}

fn after_peripheral_access(&self, clock: &pm::Clock,

_: &SpiRegisters) {

if !self.is_busy() {

clock.disable();

}

}

}

type SpiRegisterManager<'a> =

PeripheralManager<'a, SpiHw, pm::Clock>;

Now, whenever the driver wants to access the underlying SPI hardware, it goes through the manager, which transparently ensures that the hardware is ready for access before handing the reference to the driver:

impl SpiHw {

...

/// Returns the value of CSR0, CSR1, CSR2, or CSR3,

/// whichever corresponds to the active peripheral

fn get_active_csr(&self) ->

®s::ReadWrite<u32, ChipSelectParams::Register> {

let spi = &SpiRegisterManager::new(&self);

match self.get_active_peripheral() {

Peripheral::Peripheral0 => &spi.registers.csr[0],

Peripheral::Peripheral1 => &spi.registers.csr[1],

Peripheral::Peripheral2 => &spi.registers.csr[2],

Peripheral::Peripheral3 => &spi.registers.csr[3],

}

}

The particularly cool bit here is that when the driver is done with the

hardware reference, Rust will automatically Drop it, which will invoke our

after_peripheral_access method. This gives us a single place to check things

like whether this peripheral is active (i.e. doing a DMA transfer) or whether

it can be powered off.

Power management is a notoriously hard problem for embedded operating systems,

but with the PeripheralManager it’s surprisingly straight-forward. The

previous SAM4L USART driver had nineteen calls to enable_clock and five to

disable_clock, plus an outstanding clock mystery in the

interrupt handler. By centralizing clock management, driver authors no longer

have to reason through all possible execution paths to be certain they’re correctly

checking clocks everywhere. I was able to add low-power support to SPI in half

an hour and it just worked on the first try, which was absolutely mind-blowing

to me.

PeripheralManager in Action

Today, we’ve adapted the USART, SPI, and I2C drivers for the SAM4L. Look for more to move over soon, or jump in and submit a PR! We’re particularly excited to pull this into the Signpost platform, as this energy harvesting system has been artificially underperforming for a while due to the incomplete low-power implementation in Tock.

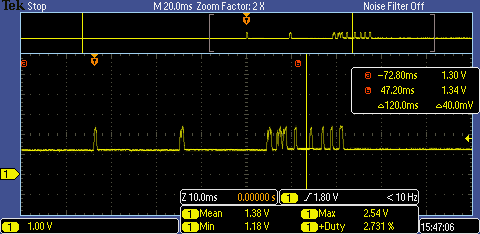

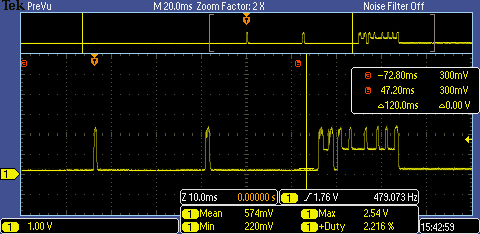

We’re just starting to move things over, so not everything is low power yet, but a lightly modified version of the Hail test app (commenting out ADC, Bluetooth, and GPIO) we can watch the baseline power draw drop:

The early, more spaced-out peaks are each of the sensor readings. The tighter

peaks at the end are all the printfs in the Hail app. The prints are

particularly interesting as you can see the USART DMA operation holding the

core in a higher power state, as well as the peaks upon each completion as the

next print is prepared.

For more details on the PeripheralManager itself, check out the

documentation.